Irish English

Phonology

Grammar

Northern Irish English

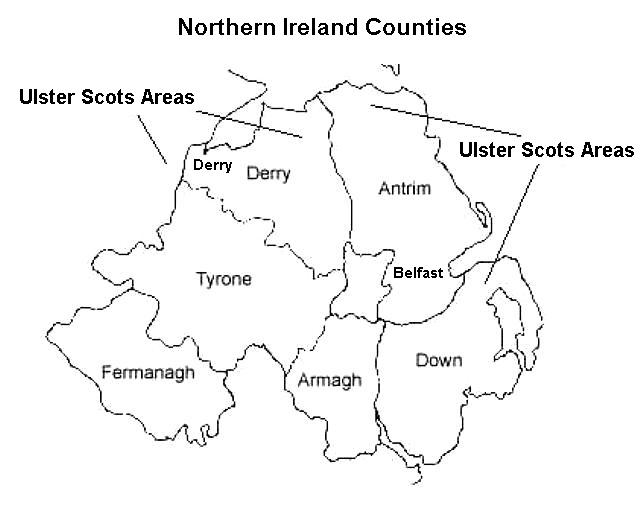

Maps

N.B. For more information on the English language in Ireland, please consult the website Irish English Resource Centre.

Historical outline In 1169 a group of Anglo-Norman adventurers arrived in the south east corner of Ireland to ostensibly help a native Irish lord in trouble with his neighbours. As so often in such situations, the helpers turned on the seeker of the help and established themselves, along with others later, in a small enclave in county Wexford. Their language was Anglo-Norman as can be seen from many early Irish loan words such as páiste ‘child’ from Anglo-Norman page, but a number of English speakers were in the retinue of the warlords.

By the end of the 12th century the Anglo-Normans had reached the area around Dublin and took the city as well with many of the English among the original settlers moving to the capital and living as traders and craftsmen there. Once established in the capital, English was never to be ousted although in other parts of the country it had a chequered career in the following centuries.

The linguistic documents from this early period have been gathered together as a group of poems known as the Kildare Poems (Heuser 1904) which must have been written sometime after 1300 (internal historical evidence).

The period of so-called Medieval Irish English lasted on in the next century and is attested in certificates, particularly in the towns of the East coast: Dublin, Kilkenny, New Ross, Waterford. The political ties of the Anglo-Normans with England became less and less with time (given the reduction in Anglo-Norman power in England after 1204 when France lost direct control over England). Hand in hand with this increasing Gaelicisation is to be seen (linguistic assimilation through mixed marriages, general acculturation). What was most important was the break with the English aristocracy after the latter converted to Protestantism.

The net result of these developments is that in the second half of the 15th and in the 16th century English receded greatly. This climaxed in the political strivings for independence which were, however, curtailed by the victory of the English over the Irish forces in Kinsale in 1601.

The seventeenth century is a watershed in the development of Irish English. During this century new settlers from England came to the south of Ireland while settlers from the Lowlands of Scotland moved across the short sea divide to Ulster. This group formed the base of the Protestant community in the north. These were furthermore dissenters and belonged to the Presbyterians (and not to the Church of England). Their variety of Scots developed further into Ulster English in the course of the following three or so centuries.

From the 17th to the 19th centuries there was a major language shift in the entire country when the rural population slowly but surely abandoned their native language Irish, switching to English as they did and developing varieties which to a greater or lesser extent show the influence of the Irish substrate. The demographic developments during these two crucial centuries were compounded by the potato famines of the first half of the 19th century culminating in the Great Famine of the late 1840’s and by the large-scale emigration to Britain (Merseyside, Newcastle, London) and the United States (north east coast, New York, Boston). These events cost the country several million inhabitants.

The English of the south of Ireland is called simply Irish English (just as one has Canadian English or Australian English). The term Hiberno-English has gone out of fashion somewhat as it is an unnecessary Latinism; Anglo-Irish is also unsuitable as this is used to refer to politics in the Republic of Ireland and to literature written in English by Irish authors.

The following sections contain a selection of the more salient features of Irish English, particular of the south with a comparison given to aspects of Northern Irish English. Note that the vocabulary of Irish English is not very different from that of British English, with the exceptions of rural terms in Ulster English. There are two recent dictionaries on Irish English, one for the south by Diarmuid O’Muirithe (1996) and one for the north by Caroline Macafee (1996).

Phonology

Plosivisation of dental fricatives A fricative realisation of the initial sounds in think and this is very much an exception in the South of Ireland. Instead the sounds are manifested as dental stops, i.e. [ṯ] and [ḏ] respectively. This applies to all but a few varieties of the South which may go further, so to speak, and use alveolar stops at the beginning of such words as think and this.

This alveolar realisation is quite stigmatised in the South and rural speakers are frequently ridiculed by imitating their speech using alveolar rather than dental stops, e.g. [tɪŋk] and [dɪs] for [ṯɪŋk] and [ḏɪs]. The ability of speakers to imitate this clearly shows that they make a distinction between a dental and an alveolar place of articulation.

The dental stop realisation of /θ/ and /ð/ may well be a contact phenomenon going back to Irish where the two coronal plosives are realised dentally, i.e. /t/ and /d/ are manifested phonetically as [ṯ] and [ḏ] respectively as in tá ‘is’ [ṯɑ:] and dún ‘castle’ [ḏu:n]. Recall in this connection that there was considerable Irish-English bilingualism up to the late 19th century before the radical decline in the numbers of Irish speakers due to the Great Famine of the late 1840’s and the subsequent emigration. Hence the suspicion that many features of Irish English derive from contact phenomena would seem to be founded.

Lenition of /t/ The normal alveolar stops of English have a further characteristic which is particularly Irish. In weak positions they are reduced to fricatives. The sound thus produced is an apico-alveolar fricative which can be transcribed by placing a caret below the relevant stop symbol, giving for instance [ṱ] as in put [pʊṱ]. The fricativisation of alveolar stops does not apply to dental stops, i.e. to those sounds which correspond to dental fricatives in mainland English, so that the contrast of word final and intervocalic /θ/ # /t/ in standard English is realised as [ṯ] # [ṱ] as in both [bo:ṯ] # boot [bo:ṱ].

Realisation of <wh> In general one can say that Irish English is a conservative variety of English. Those features which it has developed independently are by and large due to contact with Irish over the centuries as has just been pointed out. One of the conservative features which is both acoustically prominent and statistically frequent in Irish English speech is the use of a voiceless approximant [ʍ] for /w/ in those words spelt with wh. As an identification feature this is of little value as it is so common among other varieties of English, e.g. in Scottish English or many forms of American English and was still found in older varieties of Received Pronunciation according to phoneticians active early in the present century like Daniel Jones.

Morphology and Syntax

Pronominal distinctions The distinction between second person singular personal pronouns in Irish English is typical you for the singular and various forms for the plural: ye [ji], youse [juz], yez [jiz], the differential use of the latter is sociolinguistically significant, i.e. it tends to be stigmatised as uneducated and lower class.

Special word order The use of the word order OV(non-finite) to indicate a resultative perfective aspect is common: I’ve the book read ‘I am finished reading the book’ which contrasts with I’ve read the book ‘I read it once’. The object-verb word order has of course precedents in the history of English and corresponds to the original Germanic sentence brace which is still to be seen in German (Ich habe das Buch gelesen). But equally it has an equivalent in Irish in which the past participle always follows the object: Tá an leabhar léite agam lit.: ‘is the book read at-me’.

Verbal structures Irish English offers three further instances of verbal modification to indicate aspectual distinctions, two of which are probably from Irish, the third having both older forms of English and Irish as a possible source.

Habitual aspect The combination of do + be expresses habitual aspect as in He does be in his office every morning. ‘He is in his office repeatedly for a certain length of time’.

Perfective aspect After + present participle is employed to express an immediate perfective aspect as in He is after drinking the beer. ‘He has just drunk the beer’.

Durative aspect A-prefixing was found frequently but is now quite obsolete in Irish English. It has a source in English where the a is a reduced form of on much as in adverbs like alive, asleep (< on life, on slæpe): She was a-singing (cf. German Sie war am Singen). In Irish a similar construction exists: the preposition ag, ‘at’ is used with the so-called verbal noun (a non-finite verb form with nominal characteristics) Bhí sí ag canadh lit.: was she at singing.

Clefting In this connection one should mention front-focussing structures like it-clefting which are characteristic of Irish English and which have definite parallels in Irish; note that the number and kind of topicalised elements is far greater than in other forms of British English: It’s to Dublin he’s gone today. It’s her brother who rang up this morning.

Northern Irish English

The term ‘Northern Irish English’ refers to the varieties spoken in the state of Northern Ireland established with the partition of the country in 1921. The term Ulster is used synonymously by many to refer to Northern Ireland. However, Ulster is the name of an historical province in Ireland which comprises nine counties, only six of which are contained in the state of Northern Ireland, hence the further term ‘the six counties’ used by the southern Irish in preference to the official English designation ‘Northern Ireland’. The remaining three counties of Ulster, Donegal, Monaghan and Cavan are part of the Republic of Ireland though linguistically they are quite close to Northern Ireland in the characteristics which hold for their varieties of English.

Linguistically, Northern Irish English has a very distinctive prosody. This manifests itself most clearly in the fall in pitch on stressed syllables, the highlighting of which is realised in the South (and in most varieties of English for that matter) by lengthening of the stressed syllable. It is this fall which is probably responsible for the lowering of short high front vowels as in: He was hi[ɛ]t by a bullet. This feature is so salient that it alone can suffice for the recognition of a Northern Irish speaker. For the segmental speech of speakers from Northern Ireland the most easily identifiable features are the following three.

1) Retroflexion of /r/ One of the clearest dialect indicators among varieties of English is syllable-final /r/. Northern Irish English is clearly a rhotic dialect and this feature is one which those speakers who attempt to approach something like Received Pronunciation retain longest.

Syllable-final /r/ is different in both parts of the country so that one can tell a speaker just on his/her pronunciation of the word north alone. While in the southern /r/ is velarised in post-vocalic position, it is retroflex in the north so that one has [nɔɻṯ] in the south and [nɔɻθ] in Ulster.

2) Vowel length As mentioned above Northern Irish English has its origins in the language which the planters from Lowland Scotland brought with them from the 17th. century onwards. A feature which it shares with many varieties of Scottish English to this day is the lack of contrastive length in the vowel system. This applies in particular to those forms of English in the North known as Ulster Scots. Although the latter is largely a rural form of English the lack of distinctive vowel length which characterises it is also found in urban varieties of English in the north. The distinction between vowels is thus reduced to a matter of quality so that a pair of words like bid and bead are distinguished by a more central versus a more peripheral vowel articulation. In those cases where quality considerations are indifferent homophony often arises as it cot and caught both [kɔt].

The vowel shortening only applies to high and mid vowels. All short low vowels are lengthened in accordance with the phonetically open nature of such segments. This results in pronunciations like [ba:n] for ban, [ba:g] for bag, etc. with a long central low vowel.

3) Fronting of /u/ A further feature of Scottish origin in Northern Irish English is the fronting of /u/ to a mid high vowel [ʉ]. In the case of /u:/ one has shortening which leads to homophones like fool and full, both [fʉl] phonetically.