With the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834 labour shortages arose at various locations across the anglophone world. Britain sought to solve this difficulty by moving people from India, which was then a relatively densely populated country, to other countries to work on plantations owned by Englishmen. There are four particular areas where large numbers of Indians were re-settled and where the Indians later formed a clearly recognisable ethnic minority in their host country.

1) East Africa, especially Kenia, Uganda and Tanzania, where many Indians from the west of their country (Gujerat and Panjab) moved when this area was British East Africa. This continued an existing tradition of contacts across the Arabian Sea and was not necessary connected with the abolition of slavery.

Large numbers of Indians also moved to the islands Mauritius and Réunion in the Indian ocean (see light green lines in above map).

2) South Africa which received indentured servants from India between 1860 and 1911 who worked on the planatations in Natal (now Kwa-Zulu Natal). Many of these Indians were Bhojpuri from the north-west of India or Tamil from the far south.

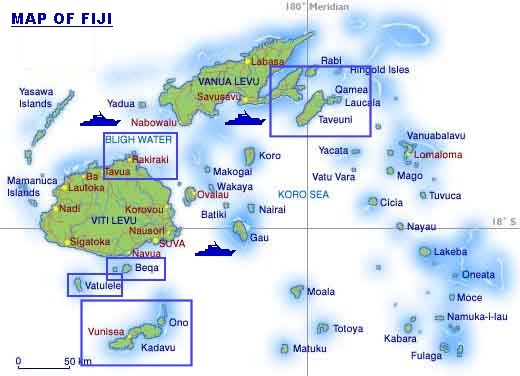

3) Fiji where Indians were moved in the late 19th century for plantation work and where they came to form the leading social group after independence in 1970, a fact which led to considerable tension with the native Fijians of Polynesian stock.

4) Trinidad and Tobago experienced an influx of tens of thousands of Indians during the nineteenth century. Some Indians came directly from India but many are the descendants of indentured labourers from other Caribbean islands. These originally worked on the sugar plantations and then on the newer plantations which produced cacao, the basis for cocoa and chocolate. The Indians of Trinidad and Tobago are mainly from the Hindi belt in the central north of the country and are ethnically Hindustanis.

In all of the extraterritorial areas where Indians settled they formed with time a burgeoning middle class. This happened in East and South Africa, in Fiji and in the Caribbean. Varieties arose in the new locations which represent mixtures of local forms of English with input from Indic and/or Dravidian languages of India.

In some cases the movement of Indians continued, albeit involuntarily. In the early to mid 1970s the Indians, called ‘Asians’, were expelled from Uganda by the dictator Idi Amin and most of them went to Britain where they have remained since.

Literature on Indian English outside India

.gif)