English in China

Nineteenth century trade with China

The Opium Wars

Legacy of British involvement

Future of English in China

Literature

Map of Asia by the 17th-century English cartographer John Speed (1542-1629)

The 19th century

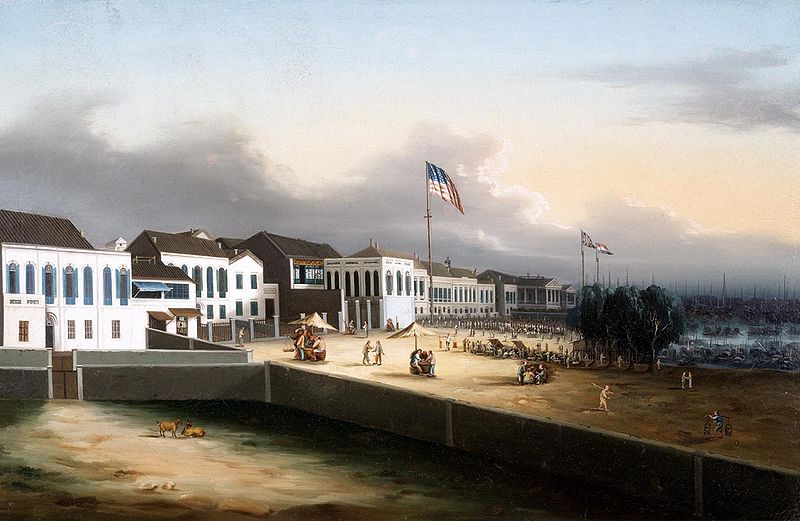

British trade with China in the 18th and 19th centuries was concentrated on the region of Guangdong (Canton) and Fujian (Fukien) which was the part of China reached first when sailing up the South China Sea.

Britain, along with other countries, established bases in China ports, such as the Thirteen Factories at Guangzhou. This trade, in which many European countries were involved, was disadvantageous to the Chinese.

The British and others forced the Qing rulers (the 19th century dynasty in China) to concede trading rights to Europeans in a series of arrangements called nowadays The Unequal Treaties (including The Treaty of Nanjing and The Treaties of Tianjin).

The opium trade with China

Opium was carried from India by the ships of the East India Company on the way to China in chests which were then used for tea when leaving China. Chinese animosity towards England arose because the British created a market of opium addicts which the Chinese authorities tried to remove.

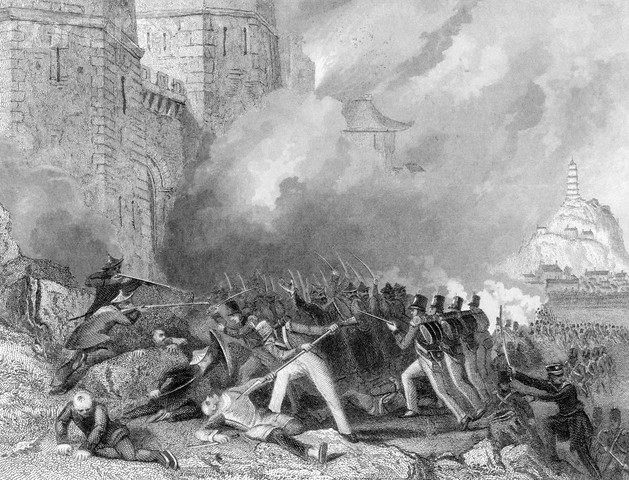

The Opium Wars

The disputes with Britain led to the Opium Wars (or the Anglo-Chinese Wars), the first one from 1839-1842 and the second one from 1856-1860. The defeat of China in these wars meant it was weakened and had to agree to a 99-year lease of Kowloon and the New Territories on the mainland of Hong Kong in 1898.

.jpg)

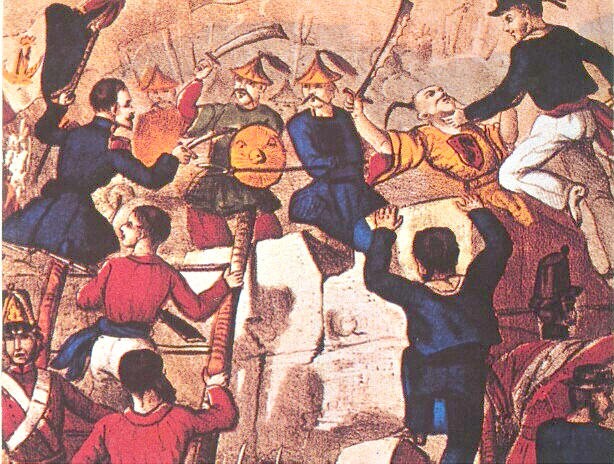

Fighting during the Opium Wars (above two pictures)

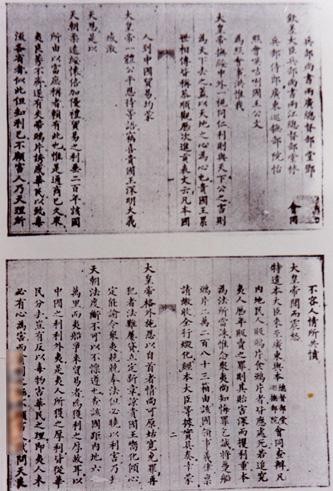

Letter by Chinese authorities to Queen Victoria requesting the termination of the opium trade (above left). Illustration of Chinese authorities destroying opium (above right)

The legacy of 18th- and 19th-century British-Chinese contacts

The main legacy of the trade contacts between the British and the Chinese in the last two-and-a-half centuries was the foundation of a British presence in Hong Kong which led to a specific variety of English arising in this city.

However, it is known that a pidgin with English as the lexifier language and Chinese (mainly Cantonese) as the substrate developed along the ports of the south and south-east of China (such as Guangzhou and Fuzhou). This pidgin never became a creole (the mother tongue of a later generation) and eventually died out with the demise of the opium trade and other types of commercial contacts between the British and the Chinese (apart from Hong Kong). Nonetheless, the word ‘pidgin’ may well go back to a Cantonese phrase bei chin (‘give money/pay’) or to the pronunciation of the English word ‘business’.

The future of English in present-day China

English is spoken as a foreign language by many millions in China today and this number is increasing every year. There are certain linguistic features of this English on the levels of pronunciation and vocabulary. Chinese do not normally pronounce clusters at the end of a word, e.g. sixth, texts, nor do they observe the distinction between /l/ and /r/ and their English has a very different rhythm from that of native speakers of English (more syllable-timed).

On the level of grammar there are prominent features of Chinese English such as the absence of the definite article, the lack of inflectional endings and different application of prepositions. These features are clearly derived from the background Chinese languages given that English is learned by the vast majority of Chinese after childhood.

However, given the great number of Chinese people learning and using English, especially in an international context, native speakers of English will probably become more acquainted with the Chinese pronunciation of English and their use of English grammar and so increased recognition will most likely be given to the Chinese manner of speaking the English language.

Literature on English in China

.jpg)