The linguistic landscape of Ireland

The linguistic landscape of Ireland

Introduction

The use of Irish

How good is the Irish?

Signs in the Gaeltacht

The use of Celtic script

The cúpla focal in linguistic signs

The enregisterment of Irish phrases

Use of Irish on nameplates

Mixtures of Irish and English

Signs in other languages

Three languages

Irish English on signage

References

Introduction

Signage in public spaces is a good indicator of language use and attitudes in a country; Ireland is no exception in this respect. In the following a selection of signs are given to document the linguistic landscape of Ireland in the early twenty-first century.

The use of Irish

Official signs, such as road signs, must be in English and Irish with the latter written in italics above the former.

The names of institutions are generally in English and Irish.

Public signs used by city and county coucils are required to be in Irish and English (with the Irish term listed first, then the English one).

Occasionally, the name is only in Irish. Garda síochána na hÉireann means ‘the peace guardians of Ireland’. Note the old spelling of the word for ‘peace’-GEN as síotcána with a séimhiú (dot) on the t and c.

Some Irish names are the originals and the English is a rendering. The word taisce means ‘treasure, store’.

The name of the following charity means ‘pity, compassion’ in Irish. Whether most Irish people know this is a moot point.

The meaning in Irish is not always the same as in English. In the following case the Irish means ‘The walled-up arch’.

In the following you can see a sign for Waterford (a Scandinavian name Vadrfjord meaning ‘the fjord of rams’). The Irish name means ‘the port of Lárag’ (a personal name). The second sign on the picture below has Woodstown Strand written on it. The Irish name means ‘sweet strand’.

Many English forms of Irish names are approximate phonetic renderings of the Irish original. In the following example the roundabout (Irish timpeallán) is called Móin na mBaintreach ‘widow’s moor’ which is rendered in English as ‘monamintra’ (note the usual orthographical errors in the Irish: there is no fada (acute accent) on the final a of the first word and the genitive plural article na is written with an uppercase instead of a lowercase n).

The English phonetic renderings can lead to pronunciations which are increasingly removed from Irish. For example, cloonlara is a common townland name (it occurs in Cos. Mayo, Clare, Limerick and Kerry) and is from Irish cluain lára meaning ‘pasture of the mare’. The vowel in the Irish word for ‘pasture’, cluain is long and is rendered, in English for this name, as /u:/ in cloon-. However, there is an increasing tendency to pronounce this as short o in English which removes the English pronunciaiton even further from the Irish original.

How good is the Irish?

The Irish used in public signage (commercial or official) often contains grammatical and spelling errors. In the following the word chun ‘for’ is written cun probably indicating that the writer used /k/ for /x/ in Irish. The word contúirteach ‘dangerous’ is spelled incorrectly and the fada (acute accent) is missing on the word snámh ‘swim’.

.jpg)

The following Irish advertisement for Guinness reads ‘Guinness the drink of energy’ but in Irish the word an fuinneamh ‘energy’ should be in the genitive an fhuinnimh.

.jpg)

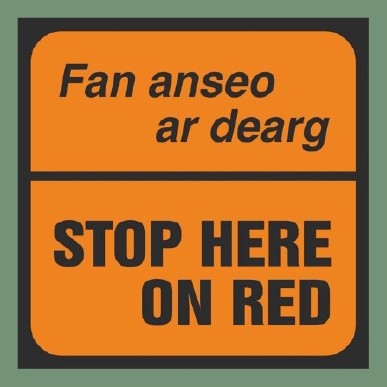

On the following sing the Irish for ‘on red’ should be ar dhearg and not ar dearg.

On this sign, meaning ‘Gorse Way’ the word for ‘gorse’ is treated as if it were feminine which it is not, the noun is masculine, Slí an Aitinn would be correct Irish.

Signs in the Gaeltacht

In the Gaeltacht areas, Irish can be used on its own, cf. the following sign which means ‘Community Hall of Corrnamona’ (north Co. Galway).

This is a billboard outside the Gaeltacht development authority industrial park. The title of the firm listed means ‘Deise Furniture, Ltd.’.

.jpg)

An old welcome sign at the entrance to a Gaeltacht area.

A similar modern sign.

A sign for a handcraft shop and a library.

This is the town shop in Rathchairn.

Road signs in Connemara, Co. Galway.

Road signs in Ring, Co. Waterford.

The use of Celtic script

Old street names are in Irish with Celtic script.

.jpg)

In the following photograph one can see the word ‘literary cafe’ on two sides of the building. On the left Celtic script is used with the Irish dot over the t to indicate that it is pronounced as /h/. Over the front of the cafe, the name is given in modern Roman script with th used for the lenited /t/ (that with the dot over it on the side).

Here is the use of Celtic script for an entirely English sign.

The cúpla focal in linguistic signs

The use of a few words of Irish by English speakers is referred, often disparagingly by Irish speakers, as the cúpla focal. Here is a shop name, simply ‘the nice shop’ in Irish. This does not mean that the shop assistant can speak to customers in Irish. The name of the pub (in Cork city), an spailpín fánach, means ‘the wandering labourer’; this is also the name of an Irish folk song. Again, the use of Irish for the name of the pub does not necessarily imply that the staff speak Irish, though this could perhaps be the case.

Music and craic (social enjoyment), an alliterating pair of words in Irish

The enregisterment of Irish phrases

Use of Irish on nameplates

Mixtures of Irish and English

Signs of languages in Ireland apart from English and Irish

A store in an industrial estate catering for the actual immigrants where they can buy their food in bulk.

Chinese and English on a restaurant sign.

Only English on this take-away sign.

Brazil and Ireland (but no Portuguese).

Signs of East European languages in Ireland

Three languages

An announcement for an Oktoberfest.

Irish English on signage

References

Government of Ireland 1958. Gramadach na Gaeilge agus Litriú na Gaeilge. An Caighdeán Oifigiúil. [The grammar and spelling of Irish. The official standard.] Dublin: Stationery Office.

Hickey, Raymond 2012. ‘Rural and urban Ireland: A question of language?’, in: Irene Gilsenan Nordin (ed.) Urban and Rural Landscapes in Modern Ireland: Language, Literature and Culture. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 17-38.

Hickey, Raymond (ed.) 2016. Sociolinguistics in Ireland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hickey, Raymond and Carolina P. Amador-Moreno (eds) 2020. Irish Identities - Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

Hickey, Raymond under review. ‘Heritage, identity and language use in public spaces in Ireland’.

Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2009. ‘Tourism and representation in the Irish linguistic landscape’, in: Elana Shohamy and Dirk Gorter (eds) Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery. London: Routledge, pp. 270-283.

Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2010. ‘Changing landscapes: Language, space, and policy in the Dublin linguistic landscape’, in: Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow (eds), Semiotic Landscapes. Language, Image, Space. London: Continuum.

Kallen, Jeffrey L. and Esther Ní Dhonnacha 2010. ‘Language and inter-language in urban Irish and Japanese linguistic landscapes’, in: Elana Shohamy, Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Monica Barni (eds) Linguistic Landscape in the City. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 19-36.

Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2014. “The political border and linguistic identities in Ireland: what can the Linguistic Landscape tell us?’, in: Dominic Watt and Carmen Llamas (eds) Language, Borders and Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 154 - 168.

Llamas, Carmen and Dominic Watt (eds) 2010. Language and Identities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Omoniyi, Tope and Goodith White (eds) 2006. The Sociolinguistics of Identity. London: Continuum Books.

Ó Riagáin, Pádraig 1997. Language Policy and Social Reproduction: Ireland 1893-1993. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Preece, Sian (ed.) 2016. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity. London: Routledge.